Chapter 1

Want to have a free flight? Take

FlightGear!

1.1 Yet Another Flight Simulator?

Did you ever want to fly a plane yourself, but lacked the money or ability to do so? Are you a real pilot looking to improve your skills without having to take off? Do you want to try some dangerous maneuvers without risking your life? Or do you just want to have fun with a more serious game without any violence? If any of these questions apply to you, PC flight simulators are just for you.

You may already have some experience using Microsoft’s ? Flight Simulator or any other of the commercially available PC flight simulators. As the price tag of those is usually within the $50 range, buying one of them should not be a serious problem given that running any serious PC flight simulator requires PC hardware within the $1500 range, despite dropping prices.

With so many commercially available flight simulators, why would we spend thousands of hours of programming and design work to build a free flight simulator? Well, there are many reasons, but here are the major ones:

- All of the commercial simulators have a serious drawback: they are made by a small group of developers defining their properties according to what is important to them and providing limited interfaces to end users. Anyone who has ever tried to contact a commercial developer would agree that getting your voice heard in that environment is a major challenge. In contrast, FlightGear is designed by the people and for the people with everything out in the open.

- Commercial simulators are usually a compromise of features and usability. Most commercial developers want to be able to serve a broad segment of the population, including serious pilots, beginners, and even casual gamers. In reality the result is always a compromise due to deadlines and funding. As FlightGear is free and open, there is no need for such a compromise. We have no publisher breathing down our necks, and we’re all volunteers that make our own deadlines. We are also at liberty to support markets that no commercial developer would consider viable, like the scientific research community.

- Due to their closed-source nature, commercial simulators keep developers with excellent ideas and skills from contributing to the products. With FlightGear, developers of all skill levels and ideas have the potential to make a huge impact on the project. Contributing to a project as large and complex as FlightGear is very rewarding and provides the developers with a great deal of pride in knowing that we are shaping the future of a great simulator.

- Beyond everything else, it’s just plain fun! I suppose you could compare us to real pilots that build kit-planes or scratch-builts. Sure, we can go out a buy a pre-built aircraft, but there’s just something special about building one yourself.

The points mentioned above form the basis of why we created FlightGear. With those motivations in mind, we have set out to create a high-quality flight simulator that aims to be a civilian, multi-platform, open, user-supported, and user-extensible platform. Let us take a closer look at each of these characteristics:

- Civilian: The project is primarily aimed at civilian flight simulation. It should be appropriate for simulating general aviation as well as civilian aircraft. Our long-term goal is to have FlightGear FAA-approved as a flight training device. To the disappointment of some users, it is currently not a combat simulator; however, these features are not explicitly excluded. We just have not had a developer that was seriously interested in systems necessary for combat simulation.

-

Multi-platform: The developers are attempting to keep the code as

platform-independent as possible. This is based on their observation that people

interested in flight simulations run quite a variety of computer hardware and operating

systems. The present code supports the following Operating Systems:

- Linux (any distribution and platform),

- Windows NT/2000/XP (Intel/AMD platform),

- Windows 95/98/ME,

- BSD UNIX,

- Sun-OS,

- Mac OS X

At present, there is no other known flight simulator – commercial or free – supporting such a broad range of platforms.

-

Open: The project is not restricted to a static or elite cadre of

developers. Anyone who feels they are able to contribute is most welcome. The code

(including documentation) is copyrighted under the terms of the GNU General Public

License (GPL).

The GPL is often misunderstood. In simple terms it states that you can copy and freely distribute the program(s) so licensed. You can modify them if you like and even charge as much money as want to for the distribution of the modified or original program. However, when distributing the software you must make it available to the recipients in source code as well and it must retain the original copyrights. In short:

”You can do anything with the software except make it non-free”.The full text of the GPL can be obtained from the FlightGear source code or from

- User-supported and user-extensible: Unlike most commercial simulators, FlightGear’s scenery and aircraft formats, internal variables, APIs, and everything else are user accessible and documented from the beginning. Even without any explicit development documentation (which naturally has to be written at some point), one can always go to the source code to see how something works. It is the goal of the developers to build a basic engine to which scenery designers, panel engineers, maybe adventure or ATC routine writers, sound artists, and others can build upon. It is our hope that the project, including the developers and end users, will benefit from the creativity and ideas of the hundreds of talented “simmers” around the world.

Without doubt, the success of the Linux project, initiated by Linus Torvalds, inspired several of the developers. Not only has Linux shown that distributed development of highly sophisticated software projects over the Internet is possible, it has also proven that such an effort can surpass the level of quality of competing commercial products.

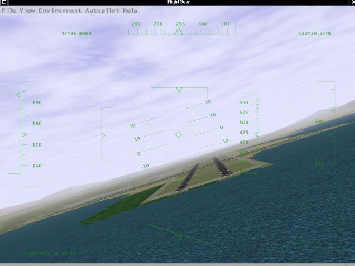

Fig. 1: FlightGear under UNIX: Bad approach to San Francisco International - by one of the authors of this manual…

1.2 System Requirements

In comparison to other recent flight simulators, the system requirements for FlightGear are not extravagant. A medium speed AMD Athlon64 or Intel P4, even a decent AMD Athlon/K7 or an Intel PIII should be sufficient to handle FlightGear pretty well, given you have a proper 3D graphics card.

One important prerequisite for running FlightGear is a graphics card whose driver supports OpenGL. If you don’t know what OpenGL is, the overview given at the OpenGL website

says it best: “Since its introduction in 1992, OpenGL has become the industry’s most widely used and supported 2-D and 3D graphics application programming interface (API)...”.

FlightGear does not run (and will never run) on a graphics board which only supports Direct3D/DirectX. Contrary to OpenGL, Direct3D is a proprietary interface, being restricted to the Windows operating system.

You may be able to run FlightGear on a computer that features a 3D video card not supporting hardware accelerated OpenGL – and even on systems without 3D graphics hardware at all. However, the absence of hardware accelerated OpenGL support can bring even the fastest machine to its knees. The typical signal for missing hardware acceleration are frame rates below 1 frame per second.

Any modern 3D graphics featuring OpenGL support will do. For Windows video card drivers that support OpenGL, visit the home page of your video card manufacturer. You should note that sometimes OpenGL drivers are provided by the manufacturers of the graphics chip instead of by the makers of the board. If you are going to buy a graphics card for running FlightGear, an NVIDIA GeForce card is recommended, as these tend to have better OpenGL support than AMD/ATI Radeon. 256MB of dedicated graphics memory will be more than adequate - many people run FlightGear happily on less.

To install the executable and basic scenery, you will need around 500 MB of free disk space. In case you want/have to compile the program yourself you will need about another 500 MB for the source code and for temporary files created during compilation. This does not include the development environment, which will vary in size depending on the operating system and environment being used. Windows users can expect to need approximately 300 MB of additional disk space for the development environment. Linux and other UNIX machines should have most of the development tools already installed, so there is likely to be little additional space needed on those platforms.

For the sound effects, any capable sound card should suffice. Due to its flexible design, FlightGear supports a wide range of joysticks and yokes as well as rudder pedals under Linux and Windows. FlightGear can also provide interfaces to full-motion flight chairs.

FlightGear is being developed primarily under Linux, a free UNIX clone (together with lots of GNU utilities) developed cooperatively over the Internet in much the same spirit as FlightGear itself. FlightGear also runs and is partly developed under several flavors of Windows. Building FlightGear is also possible on a Mac OS X and several different UNIX/X11 workstations. Given you have a proper compiler installed, FlightGear can be built under all of these platforms. The primary compiler for all platforms is the free GNU C++ compiler (the Cygnus Cygwin compiler under Win32).

If you want to run FlightGearunder Mac OS X, you need to have Mac OS X 10.4 or higher. Minimum hardware requirement is either a Power PC G4 1.0GHz or an intel Mac, but We suggest you have MacBook Pro, intel iMac, Mac Pro, or Power Mac (Power PC G5) for comfortable flight.

1.3 Choosing A Version

It is recommended that you run the latest official release, which are typically produced annually, and which are used to create the the pre-compiled binaries. It is available from

http://www.flightgear.org/Downloads/

If you really want to get the very latest and greatest (and, at times, buggiest) code, you can use a tool called anonymous cvs to get the recent code. A detailed description of how to set this up for FlightGear can be found at

http://www.flightgear.org/cvs.html.

1.4 Flight Dynamics Models

Historically, FlightGear was based on a flight model it inherited (together with the Navion airplane) from LaRCsim. As this had several limitations (most importantly, many characteristics were hard wired in contrast to using configuration files), there were several attempts to develop or include alternative flightmodels. As a result, FlightGear supports several different flight models, to be chosen from at runtime.

- Possibly the most important one is the JSB flight model developed by Jon Berndt. The JSB flight model is part of a stand-alone project called JSBSim:

- Andrew Ross created another flight model called YASim for Yet Another Simulator. YASim takes a fundamentally different approach to many other FDMs by being based on geometry information rather than aerodynamic coefficients. YASim has a particularly advanced helicopter FDM.

- Christian Mayer developed a flight model of a hot air balloon. Curt Olson subsequently integrated a special “UFO” slew mode, which helps you to quickly fly from point A to point B.

- Finally, there is the UIUC flight model, developed by a team at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. This work was initially geared toward modeling aircraft in icing conditions, but now encompasses “nonlinear” aerodynamics, which result in more realism in extreme attitudes, such as stall and high angle of attack flight. Two good examples that illustrate this capability are the Airwave Xtreme 150 hang glider and the 1903 Wright Flyer. More details of the UIUC flight model can be found at

It is even possible to drive FlightGear’s scene display using an external FDM running on a different computer or via named pipe on the local machine – although this might not be a setup recommended to people just getting in touch with FlightGear.

1.5 About This Guide

There is little, if any, material in this Guide that is presented here exclusively. You could even say with Montaigne that we “merely gathered here a big bunch of other men’s flowers, having furnished nothing of my own but the strip to hold them together”. Most (but fortunately not all) of the information herein can also be obtained from the FlightGear web site located at

The FlightGear Manual is intended to be a first step towards a complete FlightGear documentation. The target audience is the end-user who is not interested in the internal workings of OpenGL or in building his or her own scenery. It is our hope that someday there will be an accompanying FlightGear Programmer’s Guide a FlightGear Scenery Design Guide, describing the Scenery tools now packaged as TerraGear; and a FlightGear Flight School package.

We kindly ask you to help us refine this document by submitting corrections, improvements, and suggestions. All users are invited to contribute descriptions of alternative setups (graphics cards, operating systems etc.). We will be more than happy to include those in future versions of The FlightGear Manual (of course not without giving credit to the authors).

Google Advertisements - Click to support FlightGear

Latest Version

v2.0.0 - 18 Feb 2010

A new major update of the FligtGear simulator. Please check the readme

Notam

Would all pilots try and avoid mpserver02 as its often overloaded.